This new technology is making waves in the world of 3D modelling. So what are Gaussian Splats, and what makes them so fun to make?

In this article, our CEO and Co-Founder, Jeffrey Martin, gives his take on the rapid popularity of Gaussian Splatting, as well as a look under the hood at the technology behind this industry shift.

If one thing is true about the camera industry, it’s that you can’t get too comfortable. As quickly as NeRFs entered the 3D rendering scene in 2020, the technology has already evolved. Gaussian Splats are rapidly dethroning NeRFs as the latest craze for creating interactive 3D visuals, and it’s up to us to push this technology forward.

What’s in a name?

Gaussian Splatting is exactly what it sounds like, SPLAT! This creative onomatopoeia is an accurate visual representation of what’s happening within the program when you render a Gaussian Splat.

Imagine flinging paint droplets onto a canvas, where they splat everywhere in varying sizes and ellipsoid shapes. Some are more circular, others are stretched out. Some are entirely transparent, while others are opaque.

The “Gaussian” part of Gaussian Splats is named for Carl Friedrich Gauss, the 19th-century mathematician who popularized bell curves, or normal distributions. Each individual Gaussian blob is essentially a bell curve. It is an average of the characteristics of the point in space that it represents.

Gaussian Splat Pointilism

Similar to the Pointilism art style that became fashionable in the late 1800s, Gaussian Splats create a more or less detailed rendering depending on the size of the Gaussians. Millions of small dots create the bigger picture.

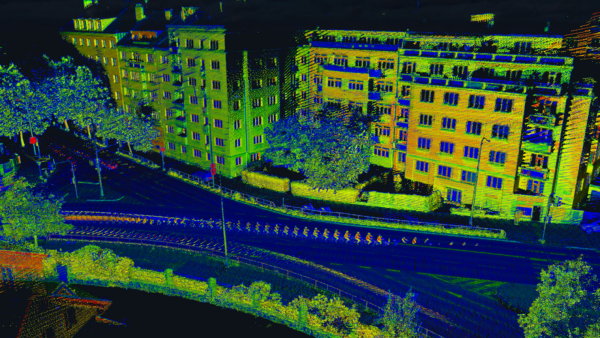

In the Gaussian Splat of this scene below, for example, the splattered ellipsoids that represent the trees and grass are shades of green. There are 7 million Gaussians present. Larger planes with no noticeable changes will create larger ellipsoids, while smaller ellipsoids of differing shades of green, white, brown, and black denote details in the rendering to reveal the entire scene.

Small Gaussians create gradients, slightly changing the shade of the scene. Shadows on the objects in the scene will appear as darker ellipsoids, while light reflecting off the surfaces appears as lighter ellipsoids. This differs from a textured mesh, whose flat triangles are unable to perceive shine and shadow, giving them a flat appearance.

Towards the bottom of the image, you see these blurry stretches of grass. That represents an area with less photo coverage, so the program has to guess what the novel view looks like between images.

When you rasterize each of the 7 million gaussians to be fully opaque, the blurry grassy areas are denoted as larger gaussians, and therefore less detailed. The image below shows that process. On the other parts of this Gaussian Splat, you can see many of the tiny, individual gaussians, but the final image of a bicycle is still obvious due to their small size. Pointillism at work.

(Photo courtesy of Dr. Dylan Ebert at Huggingface)

A fancy point cloud

Another way to look at Gaussian Splats is as a fancy point cloud. When compared to photogrammetry, Gaussian Splats have several huge advantages. They render faster, are more realistic, and represent complex surfaces more accurately.

It solves the biggest pain points of photogrammetry, such as depicting shiny objects like windows and water. Most importantly, it is an interactive medium and incredibly lightweight on the web.

Novel views: where other 3D renderings fall short

Perhaps the biggest difference between Gaussian Splatting and competing 3D rendering technology is the ability to create a novel view. In 3D visualizations, creating novel views, or a view of the scene from an angle not originally captured by the cameras, is an important technological leap.

In more simplistic 3D renderings, like panoramic walkthroughs on Google Maps Street View, you “jump” or “zoom” from cell to cell. These views were captured when photographing the scene. They captured a specific angle and cannot deviate from that perspective when you try to move around the 3D space.

This technology cannot “imagine” or fill in the gaps of what the view would look like between those angles. Nor can it transition smoothly around the scene the way our eyes would in person.

Similarly, in 3D fly-through videos, you cannot change the angle or move independently throughout the scene. You see this frequently in real estate advertisements.

Creating Novel Views with Gaussian Splatting

As you can see in the diagram above, a series of actual training images creates the entire 3D scene; however, now there is a novel view from the imaginary “camera” #4!

Gaussian Splats offer more flexibility because they can fill in the gaps to “imagine” the objects in the scene as they are positioned in space.

If you take photos in a room 1 meter apart, the Gaussian Splat can fill in the gaps between the photos, just as our brains do with missing information. Gaussian Splats are more interactive because you can move around the scene smoothly.

It is even possible for film directors to use Gaussian splatting to reshoot scenes in case they leave a set and forgot to shoot something from a specific angle. They can go back into the scene and re-film in post-production as if they were still on set.

How we got here

Gaussian Splats are a representation of a scene according to how the light reflects off the objects from where you are taking the image. That is what it means to actually perceive the world with our eyes.

We’re not looking at an object. We’re looking at the light reflecting off that object.

This concept separates a Gaussian Splat from a textured mesh. These two might seem like the same thing, but if you’re looking at an object that’s shiny or transparent, you really are looking at the light reflecting from it.

Textured mesh: the predecessor to Gaussian Splats

Meshes and textured meshes are the traditional ways to represent objects in 3D. LiDAR systems collect point cloud data. Then, the software connects the point cloud’s individual coordinates into triangles. These triangles represent the surface of an object.

Like Gaussian Splats, they follow the same principles of pointilism. Smaller triangles create more detailed textures, and larger triangles represent broad, flat surfaces.

A mesh is a monotone representation of the object. However, overlaying imagery from high-resolution cameras turns meshes into textured meshes by adding color and context.

Where textured meshes fall short

If viewing an object actually means viewing the light reflected off of an object, then a series of flat triangles is difficult for the brain to process as realistically three-dimensional.

Gaussian Splats excel in their realism because individual Gaussians can blend with the Gaussians around them. Their opaqueness is malleable, they vary in size, and their “fuzzy” ombre edges reflect light more realistically. Textured mesh triangles are more rigid, because a color is either in the triangle or not.

Therefore, textured meshes struggle to represent light reflecting off an object. Shiny and transparent surfaces, such as windows, glass facades, and water, appear flat and unrealistic.

Notice the difference in the level of detail in the fly-through video above.

The Gaussian Splats show reflections in the glass building facades and background details as far back as the human eye can see.

The textured model is still an impressive 3D rendering, but its view is limited to the objects in the foreground, and the windows are matte and static. We are missing the crucial element of light reflecting off the rendered objects.

Gaussian Splats are more than an image

It is tempting to lump Gaussian Splats into the same category as 3D photographs, but what sets them apart is their explorability.

Photogrammetry vs. Gaussian Splats

No matter how you do it, measuring objects digitally is a huge technological leap across industries.

Photogrammetry is the process of measuring 3D objects within a mesh that was created from 2D photographs.

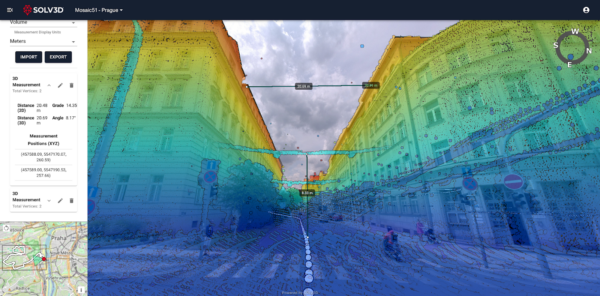

However, Gaussian Splats have a native 3D structure. Their 3D point cloud data, when viewed in aggregate, creates a model in three-dimensional space. Gaussian Splats’ faster rendering time and lower computational load make it easier to measure parameters like volume and height, for example.

Gaussian Splats and Mosaic cameras- a natural fit

Reducing capturing and post-processing time pays dividends in the world of 3D rendering. Mosaic cameras have overlapping lenses in fixed positions, which makes both steps much faster.

During capture sessions, instead of taking photos from multiple angles with one camera, a single operator can move around the scene and capture multiple images at once.

This Gaussian Splat of a Basilica was captured with the Mosaic Xplor and demonstrates the level of detail attainable with this technology.

This fixed distance between each lens also reduces the post-processing time because programs can calculate the distance and connection between each shot faster.

Mosaic mobile mapping systems are also designed specifically for large data capture projects. The built-in, removable 1TB SSD card holds a wealth of data for continuous capture in the field.

Where are Gaussian Splats heading?

As the 3D modeling and camera industries become more crucial to our infrastructure management, it is up to us to tinker with new technologies as they’re made available and to push their limits.

In the spirit of innovation and experimentation, we recently launched a huge, free resource for testing technologies like Gaussian Splatting.

The Prague RealMap is a treasure trove of 15.15 terapixels of free street-view data. Mosaic collected the imagery directly for testing purposes, and now it’s free to the public. It features over 200,000 panoramas in 13.5 K resolution from all over the downtown area.

We welcome researchers and students to use this dataset to test their theories about Gaussian Splatting, photogrammetry, and more, within non-commercial use. We even started a Discord server for collaboration and troubleshooting.

So, as far as the future of 3D reconstructions is concerned, I think that depends on what we do with the technology we’ve discovered already.

We saw how quickly NeRFs got overshadowed by the better technology that Gaussian Splats offer. Who’s to say that we aren’t on the precipice of something even better?